Feature: Powerful brain imaging creates new insights on neurological symptoms of COVID-19

By Crystal Mackay, MA’05

A multidisciplinary team of more than a dozen scientists and clinicians at Robarts Research Institute and the Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry are combining their expertise and will use powerful brain-imaging to better understand the effects of COVID-19 on the brain.

Since the virus was identified in the population just over a year ago, researchers and physicians have been observing neurological and cognitive symptoms sometimes associated with the illness.

Dr. Megan Devlin, an infectious diseases physician at the London Health Sciences Centre's Urgent COVID-19 Care Clinic (LUC3), has seen a whole range of such symptoms, including memory loss or confusion, severe headaches and loss of the sense of smell. In rare, severe cases, hospitalized patients develop stroke, she said.

“I often tell patients that each individual's experience with COVID-19 illness can be very different,” said Dr. Devlin, Assistant Professor at Schulich Medicine & Dentistry who is the clinical lead on the study. “In the same way, recovery is also variable for every individual. Some people recover from their neurologic symptoms quickly; others take many months to see some recovery.”

While they have been able to observe these varied symptoms, scientists have not yet got to the bottom of what’s happening in the brain to cause them. Since some people with COVID-19 develop blood clots and changes in blood vessels, the research team believes the neurological symptoms could be caused by the virus triggering tiny vessels to bleed in the brain -- what's known clinically as microbleeds.

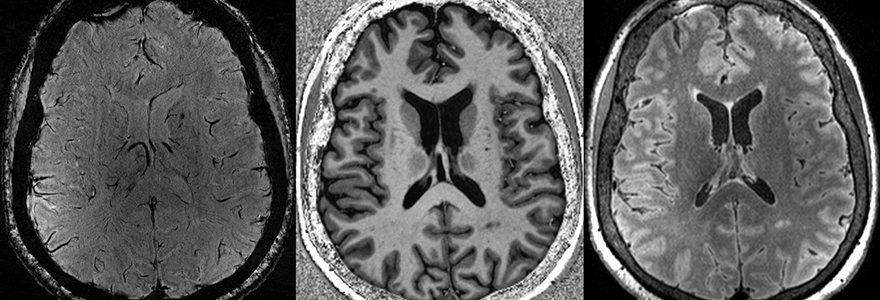

Some of these tiny brain injuries are so small that they aren’t visible with clinical brain imaging done in hospitals. However, an ultra-high-field MRI scanner at Robarts’ Centre for Functional and Metabolic Mapping is more than twice as powerful as a conventional MRI and can scan the brain in extremely high resolution.

Researchers at Robarts have developed specialized techniques to use the 7-Tesla MRI to observe even the tiniest of microbleeds. They can also pick up very subtle changes to white matter that can show where the brain has been damaged, and track changes in acidity in the brain that can indicate where it's been deprived of oxygen.

“What we are doing here is very comprehensive and unique,” said Robert Bartha, PhD, Acting Director, Strategy and Scientific Integration at Robarts, who is leading the imaging side of the study. “We are bringing together a number of very advanced measures that we’ve developed in other studies to look at multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer’s disease and epilepsy in order to try to get a fulsome picture of what’s happening neurologically in COVID-19."

The team is capitalizing on interdisciplinary research strengths including experts in brain imaging, cognitive neurology and infectious disease, Bartha said.

With the help of a $50,000 grant from Western’s Catalyst Grant: Surviving Pandemics Program, the team is hoping to recruit 60 patients who have experienced neurological symptoms from COVID-19. The researchers will do cognitive testing to observe changes in functioning after the illness and also run a full gamut of MRI scans.

“The brain is a complex organ, and these are two ways of measuring brain structure and function,” said Dr. Devlin. “We aim to see if there is a correlation between brain imaging findings and altered neurocognitive testing.”

The neurocognitive testing is led by Dr. Elizabeth Finger, Associate Professor at Schulich Medicine & Dentistry.

The hope is to determine exactly what is happening in the brains of COVID-19 patients and gain insight into what the long-term effects might be.

“One of the really interesting questions that we are hoping to answer is the effect of COVID-19 on developing other diseases later life,” said Bartha. “Any time you have a condition that causes insult to the brain, it brings in the question about whether this might accelerate the processes that leads to neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s or dementia.”